Fashion Style From the 1300s and 1400s

Clothing of the first one-half of the 14th century is depicted in the Codex Manesse. In the lower panel, the man is dressed as a pilgrim on the Style of St James with the requisite staff, scrip or shoulder-purse, and crinkle shells on his chapeau. The lady wears a blue cloak lined in vair, or squirrel, fur.

Fashion in fourteenth-century Europe was marked by the starting time of a flow of experimentation with unlike forms of clothing. Costume historian James Laver suggests that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable "fashion" in article of clothing,[1] in which Fernand Braudel concurs.[2] The draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the ancestry of tailoring, which allowed vesture to more closely fit the human being form. Also, the use of lacing and buttons allowed a more than snug fit to vesture.[3]

In the class of the century the length of male person hem-lines progressively reduced, and by the cease of the century information technology was fashionable for men to omit the long loose over-garment of previous centuries (whether called tunic, kirtle, or other names) altogether, putting the accent on a tailored superlative that fell a piffling beneath the waist—a silhouette that is still reflected in men's costume today.[iv]

Fabrics and furs [edit]

Wool was the most important material for article of clothing, due to its numerous favourable qualities, such as the ability to take dye and its being a good insulator.[5] This century saw the beginnings of the Little Ice Age, and glazing was rare, even for the rich (most houses just had wooden shutters for the winter). Trade in textiles continued to abound throughout the century and formed an important office of the economy for many areas from England to Italy. Dress were very expensive, and employees, even high-ranking officials, were unremarkably supplied with, typically, one outfit per yr, as part of their remuneration.

Mary de Bohun wears an ermine-lined mantle tied with reddish strings. Her retainer wears a mi-parti tunic. From an English language psalter, 1380–85

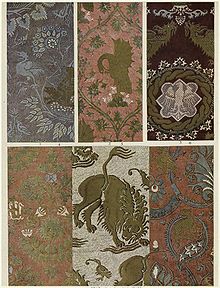

14th-century Italian silk damasks

Woodblock press of fabric was known throughout the century, and was probably fairly common by the end;[6] this is hard to assess as artists tended to avoid trying to draw patterned textile due to the difficulty of doing so. Embroidery in wool, and silk or aureate thread for the rich were used for ornamentation. Edward Three established an embroidery workshop in the Tower of London, which presumably produced the robes he and his Queen wore in 1351 of red velvet "embroidered with clouds of silvery and eagles of pearl and golden, under each alternating cloud an eagle of pearl, and under each of the other clouds a golden eagle, every hawkeye having in its neb a Garter with the motto hony soyt qui mal y pense embroidered thereon."[seven]

Silk was the finest textile of all. In Northern Europe, silk was an imported and very expensive luxury.[eight] The well-off could afford woven brocades from Italy or even further afield. Fashionable Italian silks of this catamenia featured repeating patterns of roundels and animals, deriving from Ottoman silk-weaving centres in Bursa, and ultimately from Yuan Dynasty Cathay via the Silk Route.[9]

A fashion for mi-parti or parti-coloured garments made of two contrasting fabrics, ane on each side, arose for men in mid-century,[10] and was particularly popular at the English language court. Sometimes just the hose would be dissimilar colours on each leg.

Checkered and plaid fabrics were occasionally seen; a parti-coloured cotehardie depicted on the St. Vincent altarpiece in Catalonia is reddish-brown on one side and plaid on the other, and remains of plaid and checkered wool fabrics dating to the 14th century have also been discovered in London.[11]

Fur was more often than not worn as an inner lining for warmth; inventories from Burgundian villages show that even in that location a fur-lined glaze (rabbit, or the more expensive cat) was one of the most common garments.[12] Vair, the fur of the squirrel, white on the abdomen and grey on the back, was particularly pop through nearly of the century and can be seen in many illuminated manuscript illustrations, where it is shown as a white and blue-gray softly striped or checkered blueprint lining cloaks and other outer garments; the white belly fur with the merest edging of grey was called miniver.[13] A fashion in men'due south wearable for the dark furs sable and marten arose around 1380, and squirrel fur was thereafter relegated to formal ceremonial wear.[fourteen] Ermine, with their dumbo white wintertime coats, was worn past royalty, with the blackness-tipped tails left on to contrast with the white for decorative effect, every bit in the Wilton Diptych above.

Men's wearable [edit]

Shirt, doublet and hose [edit]

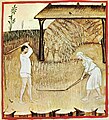

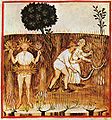

Threshing sheaf of two men, these are wearing a Braies - Luttrell Psalter (c.1325-1335)

The innermost layer of clothing were the braies or breeches, a loose undergarment, usually made of linen, which was held up by a belt.[15] Next came the shirt, which was by and large also made of linen, and which was considered an undergarment, like the breeches.[15]

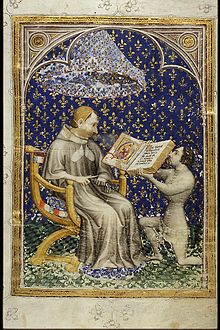

Jean de Vaudetar, chamberlain of king Charles V of French republic, presents his gift of a manuscript to the Rex, past Jean Bondol, 1372. For this very formal occasion, he is shown without anything over his tightly tailored top. The rex wears a coif

Hose or chausses made out of wool were used to cover the legs, and were generally brightly colored, and often had leather soles, and so that they did not accept to be worn with shoes.[15] The shorter dress of the second half of the century required these to be a unmarried garment like mod tights, whereas otherwise they were two separate pieces covering the full length of each leg. Hose were generally tied to the breech belt, or to the breeches themselves, or to a doublet.[15]

A doublet was a buttoned jacket that was by and large of hip length. Similar garments were called cotehardie, pourpoint, jaqueta or jubón.[xvi] These garments were worn over the shirt and the hose.

Tunic and cotehardie [edit]

A robe, tunic, or kirtle was usually worn over the shirt or doublet.[15] Equally with other outer garments, information technology was generally made of wool.[15] Over this, a human might also wear an over-kirtle, cloak, or a hood.[17] Servants and working men wore their kirtles at various lengths, including as low every bit the knee or calf. Yet, the tendency during the century was for hem-lengths to shorten for all classes.

However, in the second half of the century, courtiers are often shown, if they have the figure for information technology, wearing zippo over their closely tailored cotehardie. A French chronicle records: "Around that year (1350), men, in particular, noblemen and their squires, took to wearing tunics then short and tight that they revealed what modesty bids us hide. This was a most astonishing affair for the people".[eighteen] This way may well accept derived from war machine clothing, where long loose robes were naturally not worn in action. At this menstruum, the nearly dignified figures, like King Charles in the analogy, proceed to wear long robes—although as the Royal Chamberlain, de Vaudetar was himself a person of very high rank. This abandonment of the robe to emphasize a tight acme over the torso, with breeches or trousers beneath, was to go the distinctive feature of European men's fashion for centuries to come up. Men had carried purses up to this fourth dimension because tunics did non provide pockets.[xix]

Chaucer reading his work to the court of Richard II, c. 1400

The funeral figure and "achievements" of Edward, the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral, who died in 1376, evidence the military version of the aforementioned outline. Over armour he is shown wearing a short fitted arming-glaze or jupon or gipon, the original of which was hung above and still survives. This has the quartered arms of England and France, with a rather similar effect to a parti-coloured jacket. The "charges" (figures) of the arms are embroidered in gold on linen pieces, appliquéd onto coloured silk velvet fields. It is vertically quilted, with wool stuffing and a silk satin lining. This type of coat, originally worn out of sight under armour, was in way equally an outer garment from well-nigh 1360 until early on the next century. But this and a child's version (Chartres Cathedral) survive.[20] As an indication of the rapid spread of fashion betwixt the courts of Europe, a manuscript chronicle illuminated in Republic of hungary by 1360 shows very similar styles to Edward's English version.

Edward's son, King Richard II of England, led a court that, like many in Europe late in the century, was extremely refined and fashion-conscious. He himself is credited with having invented the handkerchief; "little pieces [of cloth] for the lord King to wipe and make clean his nose," appear in the Household Rolls (accounts), which is the beginning documentation of their use. He distributed jeweled livery badges with his personal emblem of the white hart (deer) to his friends, like the ane he himself wears in the Wilton Diptych (in a higher place). In the miniature (left) of Chaucer reading to his courtroom both men and women clothing very loftier collars and quantities of jewelry. The King (continuing to the left of Chaucer; his face has been defaced) wears a patterned gold-coloured costume with matching lid. Virtually of the men wear chaperon hats, and the women take their hair elaborately dressed. Male courtiers enjoyed wearing fancy-wearing apparel for festivities; the disastrous Bal des Ardents in 1393 in Paris is the well-nigh famous example. Men, besides equally women, wore decorated and jewelled clothes; for the entry of the Queen of France into Paris in 1389, the Duke of Burgundy wore a velvet doublet embroidered with forty sheep and forty swans, each with a pearl bell around its neck.[21]

A new garment, the houppelande, appeared effectually 1380 and was to remain fashionable well into the side by side century.[22] It was essentially a robe with fullness falling from the shoulders, very full trailing sleeves, and the high neckband favored at the English language court. The extravagance of the sleeves was criticized by moralists.

Headgear and accessories [edit]

Man wearing a chaperon, Italy, late 14th century

During this century, the chaperon made a transformation from being a utilitarian hood with a small greatcoat to becoming a complicated and stylish chapeau worn by the wealthy in town settings. This came when they began to exist worn with the opening for the face placed instead on the tiptop of the head.

Belts were worn below waist at all times, and very depression on the hips with the tightly fitted fashions of the latter half of the century. Belt pouches or purses were used, and long daggers, commonly hanging diagonally to the forepart.

In armour, the century saw increases in the corporeality of plate armour worn, and past the cease of the century the full arrange had been developed, although mixtures of concatenation mail and plate remained more common. The visored bascinet helmet was a new development in this century. Ordinary soldiers were lucky to have a mail hauberk, and peradventure some cuir bouilli ("boiled leather") knee or shin pieces.[23]

Style gallery [edit]

-

1 – Braies

-

ii – Shirt and braies

-

three – Retainer

-

4 – Cotehardie and hood

-

5 – Cotehardie

-

6 – Huntsman

-

7 – Walking

-

8 – Men's gowns

- Braies are worn rolled over a chugalug at the waist. Catalonia.

- Shirt is fabricated of rectangles with gussets at shoulder, underarm, and hem.

- Serving man wears a knee joint-length tunic with long, tight sleeves over hose. Wears a belt with a waist-pouch or pocketbook. His shoes are pointed. From the Luttrell Psalter, England, c. 1325–35.

- Benedict wears a red cotehardie, hose, and hood, Italy, 1350s.

- Man in a particolored cotehardie of carmine brown and plaid fabric, 2nd half of the 14th century, Catalonia. The cotehardie fits snugly and is buttoned up the forepart. A narrow chugalug is worn effectually the hips.

- Huntsman wears side-lacing boots, late 14th century.

- Man walking in a brisk wind wears a chaperon that has been caught by a gust. He wears a belt pouch and carries a walking stick, tardily 14th century.

- Older man (chiding an indiscreet young woman, see image below) wears a long, loose houppelande. The fashionable young men wear brusque tunics, one with dagged edges. The man on the right wears shoes with long pointed toes, late 14th century.

Women's clothing [edit]

For hawking, this woman wears a pink sleeveless dress over a green kirtle, with a linen veil and white gloves. Codex Manesse, 1305–twoscore.

Women making pasta clothing linen aprons over their dresses. Their sleeves are unbuttoned at the wrist and turned up out of the way, late 14th century

Many Italian women wearable their hair twisted with string or ribbon and bound around their heads, c. 1380

Underwear [edit]

The innermost layer of a woman'south clothing was a linen or woolen chemise or smock, some fitting the effigy and some loosely garmented, although in that location is some mention of a "chest girdle" or "breast band" which may have been the forerunner of a modernistic bra.[24]

Women as well wore hose or stockings, although women's hose generally only reached to the knee joint.[fifteen]

All classes and both sexes are commonly shown sleeping naked—special nightwear only became mutual in the 16th century[25]—nevertheless some married women wore their chemises to bed as a form of modesty and piety. Many in the lower classes wore their undergarments to bed because of the cold weather at night time and since their beds commonly consisted of a harbinger mattress and a few sheets, the undergarment would deed as some other layer.

Dresses and outerwear [edit]

Over the chemise, women wore a loose or fitted apparel called a cotte or kirtle, usually talocrural joint or floor-length, and with trains for formal occasions. Fitted kirtles had wide skirts fabricated by calculation triangular gores to widen the hem without calculation bulk at the waist. Kirtles also had long, fitted sleeves that sometimes reached down to cover the knuckles.

Various sorts of robes were worn over the kirtle, and are called by different names past costume historians. When fitted, this garment is often called a cotehardie (although this usage of the word has been heavily criticized[26]) and might have hanging sleeves and sometimes worn with a jeweled or metalworked belt. Over time, the hanging role of the sleeve became longer and narrower until it was the merest streamer, called a tippet, then gaining the floral or leaflike daggings in the end of the century.[27]

Sleeveless dresses or tabards derive from the cyclas, an unfitted rectangle of fabric with an opening for the head that was worn in the 13th century. Past the early 14th century, the sides began to be sewn together, creating a sleeveless overdress or surcoat.[27]

Outdoors, women wore cloaks or mantles, often lined in fur. The houppelande was likewise adopted by women tardily in the century. Women invariably wore their houppelandes floor-length, the waistline rising upwardly to correct underneath the bust, sleeves very broad and hanging, like angel sleeves.

Headdresses [edit]

Equally one might imagine, a woman's outfit was non complete without some kind of headwear. As with today, a medieval woman had many options- from harbinger hats, to hoods to elaborate headpieces. A woman's activeness and occasion would dictate what she wore on her caput.

The Center Ages, specially the 14th and 15th centuries, were home to some of the most outstanding and gravity-defying headwear in history.

Before the hennin rocketed skywards, padded rolls and truncated and reticulated headdresses graced the heads of stylish ladies everywhere in Europe and England. Cauls, the cylindrical cages worn at the side of the caput and temples, added to the richness of dress of the stylish and the well-to-do. Other more simple forms of headdress included the coronet or simple circlet of flowers.

Northern and western Europe [edit]

Married women in Northern and Western Europe wore some type of headcovering. The barbet was a band of linen that passed under the chin and was pinned on meridian of the head; it descended from the before wimple (in French, barbe), which was now worn but past older women, widows, and nuns. The barbet was worn with a linen fillet or headband, or with a linen cap called a coif, with or without a couvrechef (kerchief) or veil overall.[28] It passed out of fashion by mid-century. Single girls simply braided the hair to keep the dirt out.

The barbet and fillet or barbet and veil could also be worn over the crespine, a thick hairnet or snood. Over fourth dimension, the crespine evolved into a mesh of jeweler's work that confined the hair on the sides of the caput, and even later, at the dorsum. This metal crespine was as well chosen a caul, and remained stylish long afterward the barbet had fallen out of fashion.[29] For instance, it was used in Hungary until the get-go of the second half of the 15th century, every bit it was used by the Hungarian queen consort Barbara of Celje effectually 1440.

Italy [edit]

Uncovered hair was acceptable for women in the Italian states. Many women twisted their long pilus with cords or ribbons and wrapped the twists effectually their heads, oft without any cap or veil. Hair was likewise worn braided. Older women and widows wore a veil and wimple, and a uncomplicated knotted kerchief was worn while working. In the paradigm at right, one woman wears a red hood draped over her twisted and bound pilus.

Style gallery [edit]

-

1 – Italian gowns

-

2 – Barbet and fillet

-

three – Women dining

-

four – In a garden

-

v – Hood

-

6 – Italian fashion

-

7 – Bride and ladies

-

8 – Houppelande

-

- Italian gowns are high-waisted. Women'southward hair was oft worn uncovered or minimally uncovered in Italy. Detail of a fresco by Giotto, 1304–06, Padua.

- Woman presenting a chaplet wears a linen barbet and fillet headdress. She also wears a fur-lined mantle or cloak, c. 1305–1340.

- Women at dinner wear their hair confined in braids or cauls over each ear, and wear sheer veils. The woman on the left wears a sideless surcoat over her kirtle, and the woman on the right wears a dress with fur-lined hanging sleeves or tippets. Luttrell Psalter, England, c. 1325–35.

- Woman in a garden on a breezy day. Her kirtle sleeves button from the elbow to the wrist, and she wears a sheer veil confined by a fillet or circlet. Her skirt has a long railroad train. Luttrell Psalter, c. 1325–35.

- Illustration from the French Romance of Alexander, 1338–44, shows a woman wearing a red hood on her head and a dress with vair-lined hanging sleeves or tippets

- Italian style of this period features broad bands of embroidered or woven trim on the dress and around the sleeves.[30] Siena, c. 1340

- A bride wears a long fur-lined apparel with hanging sleeves over a tight-sleeved kirtle, with a veil. Her gown is trimmed with embroidery or (more likely) braid. A purple lady wears a blue drapery hanging from her shoulders; her hair is worn in two braids beneath her crown, Italian republic, 1350s.

- An indiscreet young woman wears an early houppelande and poulaines, the long pointed shoes that would exist worn through virtually of the next century past the most fashionable. Her hair is wrapped and twisted around her caput, late 14th century.

Footwear [edit]

Conservative (left) and high-fashion (correct) shoes of the belatedly 14th century

Men clothing snug boots with cuffs for fencing, tardily 14th century. These are almost certainly non cuffed boots, but rather hose which have been rolled down over garters. This was common exercise during this catamenia for workers.

Footwear during the 14th century generally consisted of the turnshoe, which was made out of leather.[31] Information technology was stylish for the toe of the shoe to be a long betoken, which often had to be blimp with material to keep its shape.[32] A carved wooden-soled sandal-like type of clog or overshoe called a patten would often be worn over the shoe outdoors, equally the shoe by itself was mostly not waterproof.[33]

Working class clothing [edit]

-

Storing olives

-

Threshing

-

Cheesemaking

-

Milking

-

Angling

-

Conveying water

-

Storing wood

-

Harvesting grain

Images from a 14th-century manuscript of Tacuinum Sanitatis, a treatise on healthful living, show the clothing of working people: men wear short or knee-length tunics and thick shoes, and women habiliment knotted kerchiefs and dresses with aprons. For hot summer work, men article of clothing shirts and braies and women wear chemises. Women tuck their dresses up when working.

See besides [edit]

- Byzantine dress

Notes [edit]

- ^ Laver, James: The Curtailed History of Costume and Fashion, Abrams, 1979, p. 62

- ^ Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Centuries, Vol 1: The Structures of Everyday Life," p. 317, William Collins & Sons, London 1981

- ^ Singman, Jeffrey L. and Will McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer'due south England, page 93. Greenwood Press, London, 2005 ISBN 0-313-29375-9

- ^ Encounter word in Laver: The Concise History of Costume and Fashion

- ^ Singman & McLean, id, p. 94

- ^ a) Donald King in Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Knightly, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, p 157, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987 and b) An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Arthur K. Hind,p 67, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in the U.s.), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- ^ Donald Rex in Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), op cit, p 160

- ^ id, p. 95

- ^ Koslin, Désirée, "Value-Added Stuffs and Shifts in Pregnant: An Overview and Case-Study of Medieval Textile Paradigms", in Koslin and Snyder, Encountering Medieval Textiles and Dress, pp. 237–240

- ^ Blackness, J. Anderson, and Madge Garland: A History of Fashion, 1975, ISBN 0-688-02893-4, p. 122

- ^ Crowfoot, Elizabeth, Frances Pruchard and Kay Staniland, Textiles and Clothing c. 1150 – c. 1450, Museum of London, 1992, ISBN 0-11-290445-9,

- ^ Georges Duby ed.,A History of Private Life, Vol 2 Revelations of the Medieval World, 1988 (English language translation), p.571, Belknap Press, Harvard U

- ^ Netherton, Robin, "The Tippet: Accessory after Fact?", in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Wearable and Textiles, Volume one

- ^ Favier, Jean, Gold and Spices: The Ascension of Commerce in the Middle Ages, 1998, p. 66

- ^ a b c d due east f g Singman and McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer's England, p.101

- ^ At that place is a famous surviving case in the Textile Museum at Lyon, chosen the "Pourpoint of Charles of Blois". It is made of highly tailored silk brocade (a total of twenty pieces of the brocade) with gold threads and lined with linen canvas. It is quilted throughout, probably stuffed with cotton. Description and photos Archived 2009-10-nineteen at WebCite and another photo, several in color. Archived 2009-10-19.

- ^ id. p. 97

- ^ Continuation of a chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis, Archives Nationales, Paris. Quoted in: Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Centuries, Vol one: The Structures of Everyday Life," p. 317, William Collins & Sons, London 1981

- ^ "Medieval Clothing Facts and information - Medieval clothing history, fashions". Ashevillelist.com. Retrieved 2012-06-12 .

- ^ Claude Blair in Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Knightly, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, Majestic Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987, p 480.The effigy and arming-coat of the Black Prince

- ^ Barbara Tuchman;A Distant Mirror, 1978, Alfred A Knopf Ltd, p456, quoting Vaughan's biography of Philip.

- ^ Laver, Concise History of Costume and Fashion

- ^ Claude Blair, in Alexander & Binski, op cit pp 169–seventy

- ^ Singman and McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer's England, page 98

- ^ History of Nightwear (German)

- ^ La Cotte Simple

- ^ a b Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, 1965

- ^ Laver, James: The Concise History of Costume and Manner, Abrams, 1979;

- ^ Payne, History of Costume

- ^ Boucher, 20,000 Years of Fashion

- ^ A Applied Guide to Reproducing 14th Century Shoes

- ^ Singman, Jeffrey 50. and Volition McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer's England, page 114. Greenwood Press, London, 2005 ISBN 0-313-29375-9

- ^ id. p. 116

References [edit]

- Alexander, Jonathan, and Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Fine art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987

- Black, J. Anderson, and Madge Garland: A History of Fashion, 1975, ISBN 0-688-02893-4

- François Boucher; Yvonne Deslandres (1987). 20,000 Years of Fashion: the History of Costume and Personal Adornment (Expanded ed.). New York: Harry Northward. Abrams. ISBN0-8109-1693-2.

- Crowfoot, Elizabeth, Frances Prichard and Kay Staniland, Textiles and Clothing c. 1150 -c. 1450, Museum of London, 1992, ISBN 0-11-290445-9

- Favier, Jean, Aureate and Spices: The Rise of Commerce in the Middle Ages, London, Holmes and Meier, 1998, ISBN 0-8419-1232-7

- Kohler, Carl: A History of Costume, Dover Publications reprint, 1963, ISBN 0-486-21030-eight

- Koslin, Désirée and Janet E. Snyder, eds.: Encountering Medieval Textiles and Dress: Objects, texts, and Images, Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 0-312-29377-i

- Laver, James: The Concise History of Costume and Fashion, Abrams, 1979

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume i, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2005, ISBN 1-84383-123-6

- Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, 1965. No ISBN for this edition; ASIN B0006BMNFS

- Singman, Jeffrey L. and Will McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer's England. Greenwood Press, London, 2005 ISBN 0-313-29375-ix

- Veale, Elspeth Grand.: The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, 2nd Edition, London Folio Society 2005. ISBN 0-900952-38-five

External links [edit]

- Medieval clothing and embroidery

- Digital Codex Manesse

- 14th Century at de Vieuxchamps [ permanent dead link ]

- The Cotehardie & Houppelande Homepage

- Translation of French 19th-century book on the history of French mode (all periods) from the Academy of Georgia. txt file

- Glossary of some medieval article of clothing terms Archived 2016-12-28 at the Wayback Car

- La Cotte Simple – a site with detailed research information and instructions on the construction of 14th- and 15th-century European clothing, especially female dresses

0 Response to "Fashion Style From the 1300s and 1400s"

Post a Comment